Human Trafficking Behind Bars and Beyond.

September 30, 2014

John Meekins

Opinion

�

Prosecution,

Sex Trafficking,

Women & Girls

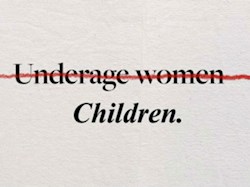

Their stories go beyond heart break, but they are true: At age 11, she ran away from home because of an alcoholic mother and a sexually abusive step-father. After three days on the street, a much older man befriended her, took her home, clothed and fed her. A few days later she was 1,000 miles away from home sitting in an Atlantic City casino bar. The bartender was paid not to notice an 11 year old girl sitting in the bar and going up and down the stairs all night long with different men. The man who was trafficking her got all the money for her services. Now 28 years old, she talks about how hundreds of these men used her to fulfill role-playing fantasies such as a father crawling into bed and molesting his daughter.

Her trafficker told her to tell the buyers she was 18 if asked. She said she could always tell they were sexually aroused by how young she appeared. When they asked her how old she really was, she replied she was “11 years-old.”

She said the buyers, anywhere from college aged students to 80 year-olds, became especially more excited.

Another woman, 21 years old, talked about a time when she was in a neighborhood known for drugs and prostitution. As a sex trafficking victim she already had been arrested once in a prostitution sting. One night she was walking home from a friend’s house in that neighborhood, and she was dragged into an alley, raped and beaten by an unknown assailant. When the police looked at her record the officer assumed she was on a “date,” and it got out of hand. Treating her as a “willing victim,” he did nothing to find the person who did it. She said the police officer should have taken her seriously and investigated further because the man who raped her could rape a little girl.

“Because the man raped me doesn’t mean he just targets older women walking alone at night. If he’s bold enough and heartless enough to attack someone innocent he could attack and rape anyone. That situation really scared me emotionally when I couldn’t even get the ones who are supposed to protect and serve to protect and serve me because of my priors.”

She went on to say, “I never really got over it. I moved on but blamed myself. I just pray I never go through that situation again.”

Too often this is the level of public service marginalized populations of society receive.

Victims Behind Bars

I have worked as a corrections officer in a women’s prison for almost 10 years. For years I had heard stories similar to these such as a 22-year-old woman who said her own mother sold her to pedophiles to pay for heroin and crack cocaine.

Another young woman related how she'd been forced to have sex with as many as 25 "johns" a night, not for her own sake but to pay her "pimp," the man who owned her. Yes, owned her.

I did not realize exactly what I was listening to, but I knew it was wrong and did not know what to do about it.

Then in May 2012 I paid to attend a two-day human trafficking conference for law enforcement and criminal justice professionals. In attendance were prosecutors and investigators from around the world including members of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Then, like adjusting the controls on a microscope, I could clearly see and realized these women were indeed human trafficking victims.

Through my new awareness, I subsequently discovered more and more inmates who were serving time for a variety of offenses but who were actually victims of human traffickers. I was not the only one who did not recognize human trafficking for what it was. In fact, too many in law enforcement don’t either. They look at a prostitute as a single person, and seldom link her to gangs and other large organized criminal organizations for which many of them are forced to work, not as employees, but as slaves.

Recruiting Within Prison Walls

This may seem like the last place human sex trafficking would occur. My experience and research suggest that a 21 year-old female getting out of after 2 or 3 years is an ideal demographic for sex traffickers. Inmates are fed, receive medical treatment and appear “healthy” at the end of their incarceration. Although “healthy,” jails and correctional institutions are too understaffed to assist the numbers of prisoners being released in finding suitable housing or job placement. There is no shortage of traffickers picking up these vulnerable inmates upon their release from jails and correctional institutions around the nation.

Too many of these women are unwittingly recruited by other inmates working on behalf of traffickers on the outside, who say, “Oh you don’t have a place to go when you get out? I have this friend he is a really nice guy and he will let you stay with him and…”

These traffickers pick the women up the minute they walk out the prison walls. The young woman getting released thinks she is going to go stay with someone for a few days until she gets a job. Instead the ‘pimp’ soon gets her high and forces her into prostitution. The chains of her enslavement are not always visible, but they are there.

A Place to Start

I certainly do not have all the answers to the problems of human trafficking how to address this complex issue, but from my experience and from what I have learned from a variety of sources some suggestions include:

1) Criminal justice standards commissions around the nation need to mandate human and sex trafficking training for all of its officers as part of the training requirements for law enforcement and corrections academies. (Judges and prosecutors need to be in here somewhere, too.)

2) Jail and prison accrediting associations such as the American Jail Association and the American Correctional Association need to implement trafficking victim identification standards as well as train their staff to identify sex trafficking recruitment rings operating within their facilities (especially in female institutions).

3) Government cannot do everything. Law enforcement and criminal justice agencies need to partner with non-government organizations (NGOs) in their communities to work with their inmates and assist with re-entry efforts for female inmates. Many resources can be found at the Polaris web site, which includes lists of resources by state. Polaris can also provide referrals and training resources.

4) Since many victims are reluctant to self-identify themselves because of embarrassment, fear, shame or distrust of law enforcement they still need to be given every opportunity to report what has happened to them. Inmates in most states are restricted to calling all but a few pre-approved phone numbers; I suggest having jail and correctional institutions allow the number for the National Human Trafficking Resource Center be made available (1-888-373-7888).The number needs to be posted next to phones. The signs should be in English and Spanish. They are a relatively very low cost step that can change and even save lives.

Topics:

Prosecution,

Sex Trafficking,

Women & Girls